So there I was, alone in the upstairs bedroom, snooping through Iki's photos. I was about to put them down and move back to my little encampment on the floor when I noticed the laminated image taped to his metal briefcase. It seemed to an advertisement that featured him holding a bottle of MOET champagne while he did a variation of his "Japanese geisha boy" pose. I was trying to puzzle out the writing on it when I heard someone coming up the stairs. I rushed back to my rolled-up futon and leaned back, pretending to read a book.

In walked the Kashira. Ishikawa, still in a mawashi, followed the Kashira through the door with a pile of his clothes folded into a neat pile. Ishikawa gently placed the Kashira's clothing on a cushion on the floor, while the Kashira sat down on the tatami and lit a cigarette. He asked me what I was reading.

"It's about boxing," I said.

He replied with a Japanese phrase that literally means, "That stinks like a geezer." He meant my book sounded square; something only a grownup would read.

"It's pretty interesting," I told him.

The Kashira grunted, but Ishikawa outed him. "The Kashira has shelves full of serious books," he said.

Then the Kashira asked me if I'd ever seen a Japanese yakuza movie. I named some of the noirish Kurosawa movies I'd seen, but that wasn't what he was looking for. "Do you know Akira Kobayashi?" he asked.

I told him I didn't and he named a movie he thought I should see.

By this time, he had undressed for his bath and was wearing a towel around his waist. He disappeared through the sliding door and I went back to my book. Not long after that, Iki came back. He quickly undressed, wrapped a towel around his own waist, and went downstairs.

Now, there are few inviolable restrictions placed on me, as more or less a guest, at the stable. One is that I can't lie with my feet facing the dohyo. But another is that I'm not to bathe until the Oyakata, Sekitori and Kashira have done so. They each prefer to bathe alone—or, in the Sekitori's case, with a tsukebito—and no one would dare deny any of them this privilege. But now, it looked like Iki did exactly that. It appeared like he barged in on the Kashira during his bathtime. How could he possibly get away with that? I wondered. It wasn't hard to imagine that he was involved with organized crime; maybe he was some member of a yakuza elite whose position trumped that of anyone in the stable.

He came back in about ten minutes and changed into the clothes he was wearing earlier: plaid shorts and a red t-shirt with white characters sewn onto it that said "AI," which means "love." It used to say "DAVID," he told me, but he tore off the D, V and D.

When he sat down, I pointed to his briefcase with the strange advertisement on it and asked, "Is that you?"

"Yes," he said, then tapped the first two Chinese characters at the top of the page.

"I can't read that," I said.

"Baishu," he read for me. I told him I didn't know what that meant.

"Soap, you know?" he said. That I did know. "Soap" is short for "Soapland" which is also known as "The Turkish Baths." It's a form of prostitution available in Japan that involves having one's body vigorously scrubbed with that of a naked sudsy woman. I don't know exactly what else it involves, but can only assume the most unsavory.

But before he could tell me how he and the bottle of MOET figured into the arrangement, the Kashira walked in. Iki cut off his explanation and fell silent. The room was now tensely quiet, and I wanted to get out. Since the Kashira was now out of the bathroom, I knew I could bathe so I started looking for my towel, but couldn't find it.

I finally spotted it over by Iki: he'd apparently stolen it from my pile of things before he'd gone to the shower. I'd share a towel with just about anyone at the stable, but I could only imagine what sort of secret dermatological infirmities Iki suffered from. Fortunately, the Kashira asked me what I was looking for and, when I answered, commanded Ishikawa to fetch me a clean towel from somewhere.

After my bath, I went downstairs to eat some of the mochi that the wrestlers had made. It was easily the best mochi I'd ever had: fresh and hot, chewy without being rubbery. The Kashira's wife, daughter and little grandson worked together with a friend of the family, molding the mochi into oblong balls and cutting it into chunks. They served it under mounds of shredded daikan, sugary black beans, sweeted soybean powder, and natto. All, except the natto—which I skipped—were delicious. Stuffed, I went back upstairs to hang out until the bon-en-kai, while the wrestlers took their naps.

A bon-en-kai is sort of like a New Years' party, except it doesn't fall on New Year's. It literally means, "forget the year party," and considering the amount that is imbibed at a typical bon-en-kai, much of the year is indeed likely to be forgotten.

One of the reasons why I remained at the stable longer than intended was so I'd be around for the bon-en-kai. The Oyakata originally said he thought I'd get what I needed from living in the stable in a week to 10 days. He said I could stay around longer if I wanted, but I interpreted that as him just being nice. So I thought I would leave two days after Christmas, which would have had me at the stable for 10 nights.

Then, toward the end of my stay, wrestlers started asking me if I'd be there for the bon-en-kai. They told me it would be fun. I was flattered that they wanted me around and thought it would be cool to see the guys outside the stable, maybe with a little bit of liquor in them. Plus, I saw it as a way to bring some closure to the experience. When I asked the Oyakata if I could hang around for a few extra nights, he said, "Sure, no problem."

When the wrestlers woke from their naps, they began putting on layers of sumo clothing—their button-up undershirts, robes, sashes—in preparation for the party. Iki had changed too, into a vaguely shiny dark gray suit, with a gold necklace over his collar and under his tie. He'd been working his cell phones furiously for nearly an hour; I couldn't make out what he was talking about, but I heard him mention a string of women's names in the diminutive form: Tomoko-chan, Hiromi-chan, Etsuko-chan. Maybe he was procuring hostesses—or strippers!—for the bon-en-kai, I thought. Maybe now I'd witness why they let this guy hang around.

I followed the crowd out of the stable to the spot near the train station where they said the party would be held. It turned out to be a "snack bar" in the basement of a commercial building across from the station. Snack bars, in Japan, are not kiosks that sell soda, hot dogs and potato chips. They're little bars, most with a small but regular male clientele. They usually have karaoke machines with a generous selection of "enka," which are melodramatic synth-folk songs about lost love and broken dreams. One representative enka tune boasts the refrain, "Please let me have some money before you leave me."

Snack bars are generally run by a handsome, if aged, proprietress and sometimes an attentive younger staff. But now this basement snack bar was empty, rented out for the stable's party: the perfect site for the wild sumo bacchanalia I suspected Iki had planned.

We filed into the narrow bar. I took a spot on the long black vinyl sofa that ran the length of the room under a mirror. Hiroki sat next to me and Batto across the table. There was a karaoke stage at the front of the bar, done up in a Hawaiian motif.

No one said much. A guy in a white shirt and black bowtie came out of the kitchen and placed some trays of sushi on the tables. I sat back and waited for the madness to begin.

Then, suddenly everyone stood up. "Otsukarisandegozaimasu!" they belted out, as the Oyakata walked in. He was holding his grandson's hand and was trailed by his wife and daughter. The evening suddenly looked much tamer than I'd expected.

And indeed it was. Not only were there no hookers, the wrestlers barely even drank, most of them sipping iced oolong tea once they'd gotten past their obligatory beer toasts, during which the Sekitori shared his wish for everyone to advance up the banzuke in the coming year.

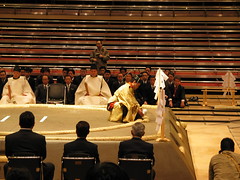

But the party did give me the sense of closure I was looking for. It was like a reunion of the characters I'd met over the past couple weeks. Everyone was there: the wrestlers, their hairdresser, the bald gyoji, the yobidashi who came to help make the dohyo.

I looked up at one point and saw the Kashira chatting with the Sekitori, who was absent-mindedly poking Kazuya between the neck and collarbone with a folded fan. I saw Murayoshi chastise Hiroki for singing too softly just like he had in the ring the previous morning for letting himself be thrown to the floor. "I'm sorry," Hiroki replied deferentially. I watched Iki flit from table to table, making smalltalk, pouring drinks, entertaining the Oyakata's grandson.

Eventually, it became my turn to sing a karaoke tune. I ordered up "Back in the U.S.S.R." and took the stage, hamming up the "Georgia's really on ma-ma-ma-ma-ma-ma-ma-ma-ma-mind" part. After I sang, Moriyasu called me over to the Kashira, who tried to give me a rectangle of 1000-yen bills folded together. I'd noticed that the wrestlers were getting something from the Kashira after they sang, but hadn't been able to tell what.

"What's that for?" I asked Moriyasu.

"For singing," he said. "Everyone who sings gets money. It's part of the bon-en-kai."

"I can't take any money," I said.

"Sure you can," he said. "You have to—you sang."

"I'm sorry, I can't," I said. Moriyasu looked hurt. He gave up on me, but the Kashira thrust the bills at me again.

"It's for singing," he said.

"Thanks," I said. "But I'm sorry, I can't take that."

"Why?" he asked, confused.

"I'm a journalist," I answered, sounding grander than I'd intended. The young gyoji Kichijiro, with whom he'd been drinking, managed somehow to explain what that implied, and I was off the hook.

"But I'll take some of this," I said, pointing to the bottle of sho-chu they'd been sharing. The Kashira poured me a cocktail of sho-chu, a vodka-like liquor, and water with a splash of canned black coffee. It was very good.

I spent the rest of the party drinking sho-chu with the Kashira, Kichijiro and Ishikawa, listening to the wrestlers sing pop songs, while the old guys sang enka tunes of loneliness and despair. Then we all walked back to the stable.

NEXT:

Stablemates III