The Big Dohyo-Matsuri

The day after I saw the wrestlers train in front of the yokozuna promotion council, Miki, the Yomiuri reporter who'd arranged my stay at the stable—and whom I still hadn't met in person—sent me an email. He wrote that the sumo association was going to hold a dohyo-matsuri on Saturday morning to sanctify the ring at the Kokugikan before the start of the January tournament. He invited me to drop by and said he would meet me there afterwards.

I arrived late and by the time I got there, a small crowd had formed along the roped-off entrance to the stadium. People held cameras and craned their necks for a clear view of whoever was supposed to emerge from the doors. Leaning against the doors were two almost billboard-sized paintings of wrestlers, whom I recognized from the sumo magazine I bought a few days earlier.

One was Kaio, standing with his muscular arms at his side; the other was the Mongolian yokozuna Asashoryu, pictured kneeling midway through an elaborate shiko. Both wore the ornate apron-like kesho-mawashi that designated their advanced rank. Asashoryu wore a broad rope around his waist with lightning-bolt-shaped paper cutouts hanging between his crouching thighs. The rope and cutouts identified him as a yokozuna.

These portraits, I later learned, memorialized the wrestlers' victories in the tournaments held last year. Asashoryu had won five championships; Kaio had won only one.

At first I thought that the crowd was waiting to get into the dohyo-matsuri, but now and then a guard would usher someone through the pack and into the entrance. I worried I was missing the ceremony inside, so I wandered over to the side entrance by the sumo museum and walked in without being stopped. I saw a guard and asked him where the dohyo-matsuri was being held; he motioned toward a nearby set of three doors. I assumed my jacket and tie were affording me this unfettered access.

I stepped through the doors and into the enormous wrestling hall. The dohyo was at its center, set into a raised trapezoid of packed earth barely larger than the ring itself. A wooden Shinto-style roof was suspended over the dohyo, with thick red, white, black and green tassels hanging from each corner. These four tassels are said to represent the four seasons, the four points on the compass, or four mythical beings, depending on whose explanation you're reading. But nobody seems to dispute that they at least symbolize the four pillars that once supported the canopy.

Until the 20th century, sumo matches were held outdoors, often in dohyo under canopies to protect wrestlers from rain and snow. When the sport moved inside the Kokugikan (literally, "national sport hall") that was built specifically for sumo matches in 1909, the roof came with it. But now that matches were held indoors, the roof served no practical purpose and the pillars that supported it blocked spectators' views of the ring. So in the 1930's (or the 1950's, depending, again, on your source), the thick tassels replaced the pillars.

The canopy itself, meanwhile, was modeled after the roofs that cover many Shinto shrines. I've read that it bears an especially close resemblance to the roof of the Ise Shrine in Mie prefecture. The Ise Shrine is dedicated to the Sun Goddess that, according to Japan's native cosmology, began Japan's imperial line. This makes it one of the country's most important religious sites.

But while the Ise Shrine was established millennia ago, it has only shared roof styles with sumo dohyo since the 1930's, when it was introduced to the Kokugikan to make sumo look more classically Japanese. Before then, the canopy over the dohyo was modeled after roofs of traditional farmhouses in the Japanese countryside.

Around the dohyo were two tiers of seating. The lower tier consisted of floor seating with 15 gradually sloping levels of corrals divided by calf-high metal rails. Each corral was just large enough for four people, and four square cushions divided the orange-carpeted enclosures into quarters. A small wooden tray with four ceramic teacups waited in the center of each corral. Below the levels of corrals, there were a few rows of cushions directly on the ground around the dohyo. The upper mezzanine tier extended over the corrals on the lower levels and was made up of 15 or so rows of red folding seats.

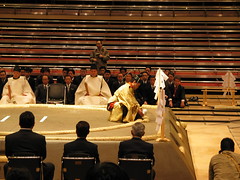

A few spectators, mostly lone watchers who had claimed a coral for themselves, watched the dohyo-matsuri, which seemed to be following the same basic sequence as the one I saw performed at the stable. But this one was far more intricate, with three gyoji performing the rites, each looking more explicitly priestly than Hage-san. Unlike Hage-san's flamboyant costume, their formal hats and robes were identical to the vestments worn by actual Shinto priests. The main gyoji, who recited the prayers, wore a gold robe; the other two wore white ones.

The dohyo was surrounded by Oyakata and other sumo functionaries in dark suits. They shared the sake and other offerings that the wrestlers sampled at the dohyo-matsuri I watched at the stable.

When the ceremony ended, I followed the small audience outside, where the crowd around the front entrance had grown. Soon after I joined the crowd, Kaio and Asashoryu emerged from the building wearing formal kimono. I recognized Kaio's ursine face from when he appeared before the yokozuna promotion council. But I'd never seen Asashoryu in person and was surprised by how young he appeared with his pudgy unlined face.

An older Japanese man ceremoniously handed each of them a smaller version of the giant portraits of themselves that they now stood in front of. I couldn't make out who the old guy was, but assumed he was either a member of the sumo association or a representative from the Mainichi newspaper, which commissioned the paintings. When he handed Asashoryu his portrait, a short, old Japanese woman in front of me remarked bitterly to an equally short old woman beside her: "He just came back from Mongolia last week."

Then the two wrestlers edged up close to one another and shook hands for the cameras that everyone in the crowd seemed to be holding. "You go, Kaio!" shouted the old woman in front of me.

Indeed, with the tournament a day away, the question that seemed to be on the minds of all sumo fans was whether Kaio would perform well enough to become a yokozuna in this tournament. Japanese fans, I had read, were tired of having a foreigner alone at the pinnacle of their national sport. They wanted a Japanese yokozuna.

But, so far, Kaio's chances didn't seem very good. He had suffered multiple losses to lower ranked wrestlers during the yokozuna promotion council session—I even saw one of the oyakata there publicly chide him for losing so many matches, though I didn't know who he was at the time.

Some fans and commentators blamed his poor performance before the council on Asashoryu. The yokozuna missed the session, his oyakata said, because he had returned from his New Year's vacation in Mongolia with a cold. Kaio lost so many matches because he had to pick up Asashoryu's slack and fight more than he would have otherwise had to, some were saying.

Implicit in many fans' comments, it seemed to me, was some resentment that Asashoryu had left Japan for the New Year's holiday.

"It's been a longstanding tradition in the sumo world that wrestlers wait and take their New Year's holiday after the year's opening tournament," wrote one commentator in the Asahi newspaper. "If Asashoryu loses several matches [because of his illness], he will likely receive the criticism that he deserves."

I don't think this bitterness stemmed from resentment over a lack of a Japanese yokozuna. Instead, I feel like Japanese see Asashoryu as not living up to the demands of his esteemed position.

Sumo wrestlers dress like Japanese of centuries past, surround themselves with emblems of Japan's native religion and observe traditional Japanese social mores and customs with a greater gusto than the rest of the population. In all this, they are kind of like a distilled version of an exaggerated form of Japanese-ness. So the sport's sole champion should be an exemplar of Japanese behavior, whether he's Japanese or not. Slacking off on pre-tournament practice after splitting for Mongolia just wasn't becoming for a yokozuna, the subtext seemed to be.

At any rate, once the brief award ceremony ended, the crowd dispersed and the rope boundary was taken down. I wandered back into the Kokugikan to kill time until I heard from Miki, from whom I expected a phone call.

NEXT: Eko-in

<< Home